Introduction:

Twenty years ago, Africa decided to turn to integration and transformation, and away from a divided

and fractured continent, where leaders ran their countries like fiefdoms. At the time the

Organization of African Unity had little or no credibility to hold heads of governments and states to

account, due to its weak and irrelevant mechanisms, that were outmoded in a new world of

integration. Africa rose to the challenge, and through bold leadership the Constitutive Act of the

African Union was born, at beginning of the millennium.

Central to this evolution was the issue of governance; a concept that aimed to ensure that the

African citizenry have the right to demand to be governed well. The premise being that with good

governance came everything else- faster economic growth and political stability, a more transparent

and accountable leadership, functioning democratic institutions, better service delivery, wider and

more deepened culture of rule of law, diverse participation and freedom of expression. This period

of rapid transformation of continental policies gave much optimism to a point where the

transformation was dubbed the African Renaissance, referring to bold initiatives to provide

frameworks that facilitate dialogue between governments and their people, African leaders and the

international community, grater convening power for Africa to act as block and safeguard its

interests. At least 22 new conventions and treaties were added to another 21 prior to the

Constitutive Act, which is now 20 years old. Added to this were also many other treaties that

expanded the parameters of governance and political participation, one of which was the African

Charter on Democracy Elections and Governance, the most relevant document now, to Africa’s

adherence to popular participation, credible periodic elections, strong institutions, etc… The

plethora of norms aimed to guide us into an era where an Africa is better governed, pointed towards

progress and a trajectory where democracy by dialogue was beginning to the cultivated and

nurtured as a culture and one of the core principles of Africa’s Shared Values.

However, these aspirations have unravelled at an alarming pace over the past decade. Executive

power is gradually being increased at the detriment of other arms of government, creating a skewed

relationship, and upsetting the concept of separation of powers. Parliaments are increasingly being

weakened. State, regional and even continental institutions are being hollowed out and rendered

ineffective and incapable to prevent, and respond to crisis. The rise of authoritarians, corruption and

poor governance, constitutional tampering, term elongation, election malpractice, to name but a

few, has resulted in deep instability and attendant insecurity in the region. There were also 23

attempts to modify or eliminate term limits in: Algeria; Burkina Faso, Burundi; Cameroon; Comoros;

Chad; Cote d’Ivoire; DRC; Djibouti; Egypt; Gabon; Guinea; Rep of Congo; Nigeria, Niger, Rwanda;

Togo; South Sudan; Uganda. Some of these countries have changed their constitutions multiple

times to achieve the aims of elongation of tenure of the respective presidents. There were at least

29 armed conflicts in Africa over the last decade. These conflicts do not include clashes over

elections flares, or intra community conflict, and sectarian violence.1

Senegal: Seen as one of the most stable countries in Africa, and a pillar of democracy and good

governance, the country has recently been rocked by protests and political violence. There has been

evidence of unprecedented closure of public space, arrests of political opponents, systematic

repression of the opposition, intimidation of journalists and activists, and the constant attack on civil

liberties. Demonstrations are strictly controlled,(although the ban had not ben enforceable), and

policing of the public space has been militarized. However, the increasing and continued violation of

democratic principles and practices is not new in Senegalese political arena but it is critically

intensifying as the country heads towards the end of President Sall’s second final termconstitutionally- in 2024. This is a crux of the disruption in Senegal- the issue of possible term

elongation.

President Sall appears to be pushing for third term through a broad interpretation of Article 27 of

Law No. 2001-03 of January 22, 2001 of the Constitution on term limits which states: “The term of

office of the President of the Republic is five years. No one may serve more than two consecutive

terms.” The incumbent had a seven years-term from 2012 to 2019 and because of the 2016

constitutional amendment that reduced the term to five years. He was re-elected to serve for 2019

to 2024. Despite the clear provisions in the constitution on term limit, President Macky Sall revealed

in the Express interview that: “When the time comes, I will make my position known, first to my

supporters, then to the Senegalese population” A similar scenario happened in 2012 with Sall’s

predecessor, President Wade, also expressed the will and determination to run for a third term. His

candidacy was approved by the constitutional council, in the context of a very tense political crisis

that cost the lives of a dozen people. Wade forged ahead with his term elongation ambition and lost

at the runoff to Macky Sall. The current political rivalry between Sall and Ousmane Sonko, a political

opponent that has been embattled with various court cases, many see as politically motivated, is

increasingly toxic.

The incessant and determine push for a third term, by Sall, has also created a polarized political

crisis between pro and anti-third term groups. This can have disastrous consequences for country as

well as the region, which is facing critical security issues ranging from military coups and regimes in

Mali, Burkina, and Guinea- to insecurity, terrorism, communal and sectarian violence, as well as debt

and economic distress, food insecurity and energy crisis.

Sudan: Tensions between Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who is the military commander of the

Sudan’s Armed Forces (SAF) and has for years been the de facto leader of Sudan, and Gen.

Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, (Hemetti), leaders of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), reached boiling

point and erupted into fill blown war on 15 April, 2023. Despite regular warnings from civil society,

grassroots political leaders, and political parties, that the situation would unravel, after the second

coup took place on 25 October 2021. The fighting is a struggle over control of the security sector,

exercise of power and access to resources of the state. The timing and sequencing of the integration

of the RSF forces in the SAF has been one of the main sticking points. RSF maintain that reforms for

a more inclusive, professional military are needed before its forces integrate. Its leader, Hemeti, also

wanted to maintain his own paramilitary as a security guarantee up the elections (which have not

been agreed to and finalized). Contrarywise, the SAF expressed fears that the proposed reforms

could hollow out the military and leave it open for the RSF to over power and dominate it. Other

issues also point to a major trust deficit between al-Burhan and Hemetti, as well as the growing role

and influence of external actors such as Egypt, Libya, UEA, Saudi Arabia, Eretria and Ethiopia, who

have all taken sides in the conflict.

More than a million citizens are displaced, with tens of thousands flocking to neighbouring countries.

The diplomatic and consular corps as well as UN/INGO political and humanitarian workers have also

left the country, (ostensibly Khartoum, where to war is most fierce. However, hundreds of

thousands of Sudanese citizens remain trapped I the urban war. In addition, up to 100,000 refugees

in Sudan have been forced to flee back to their countries of origin, including 60,000 who have fled to

Chad, while others have attempted to return to Ethiopia (currently only allowing foreigners to cross

the country), and South Sudan. The country is also experiencing fighting in other parts of the country.

Almost 16 million people are estimated to need humanitarian assistance across the country in 2023

because of a complex crisis, up from 14.3 million in 2022. A socioeconomic crisis characterised by

high inflation rates and currency depreciation, and food insecurity affecting nearly a quarter of the

population. Intercommunal clashes and violence in some areas of the country, especially in Darfur

and Kordofan regions, also contribute to the high numbers of internal and cross-border

displacements. A severe flooding season between May–September 2022 (typically between June–

September) also affected 16 out of 18 states in Sudan.

This event interrogates the country situations of the two AU member states through the lens of the

nationals of the respective countries. It seeks to elicit solidarity with the citizens of the countries

being discussed, proffer policy options on the uniquely different challenges (former being trapped in

term an elongation project for political dominance by a head of state, whose term is running out,

and deploying methods of suppression of popular participation and good governance; and the latter

spiralling into to total chaos and conflict that has witnessed mass deaths and exodus of refugees).

Yet, both countries actions have a very possibility of plunging their respective neighbourhoods into

total disarray and reginal instability. The event will bring together HRDs attending the 75th Session

of the ACHPR, as well as diplomatic and consular corps based in The Gambia, and government

officials, as well as media.

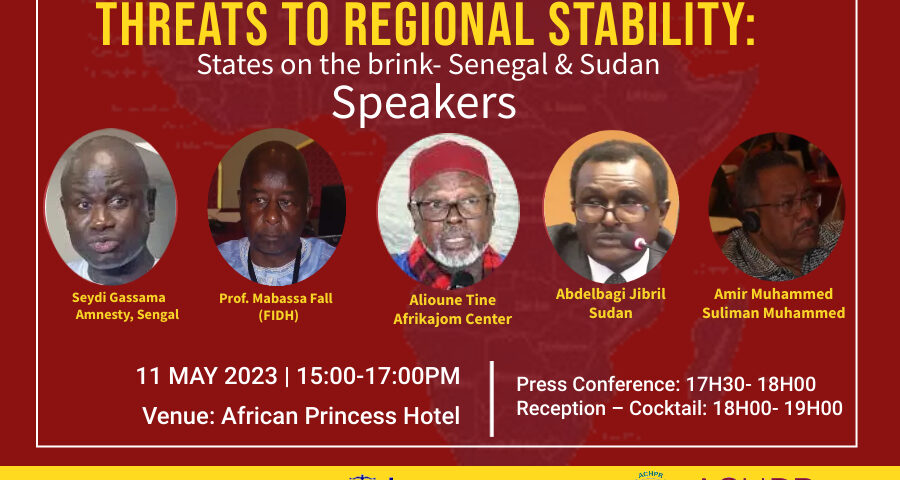

When: Thursday 11 May 2023

Venue: African Princess Hotel

Time: 15H00- 17H00

Press Conference: 17H30- 18H00

Reception – Cocktail: 18H00- 19H00

Speakers

Senegal:

Alioune Tine, Afrikajom Center

Seydi Gassama, Director Amnesty, Senegal

Prof. Mabassa Fall, International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Sudan:

Amir Muhammed Suliman Muhammed

Abdelbagi Jibril

About the Organizers

The African Commission on Human And Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR)

The African Charter established the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The

Commission was inaugurated on 2 November 1987 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The Commission’s

Secretariat has subsequently been located in Banjul, The Gambia. In addition to performing any

other tasks, which may be entrusted to it by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, the

Commission is officially charged with three major functions: the protection of human and peoples’

rights; the promotion of human and peoples’ rights; the interpretation of the African Charter on

Human and Peoples’ Rights. The Commission consists of 11 members elected by the AU Assembly

from experts nominated by the State Parties to the Charter. Their mandates are for six years,

renewable. The Commission will host the 75th Ordinary Session.

The African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies (ACDHRS)

The African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies (ACDHRS) is independent, non-profit

regional human rights NGO based in Banjul, The Gambia. It was set up in 1989 by an Act of

Parliament of the Republic of The Gambia. However, 1995, the African Centre was re-launched,

thereby repealing the Act, and thus making the Centre a truly independent, autonomous and panAfrican NGO. The Center will host the CSO Forum on the margins of the 73rd Ordinary Session of the

Commission.

Open Society–Africa

Open Society–Africa is a regional entity of the Open Society Foundations’ and aims to deepen

people-centered democracy, accountable governance, and inclusive development in Africa through

strategic grant making, convening power, investment in African knowledge production and people

centered advocacy, focused on promoting open societies, accountable governance, human rights,

sustainable development and just climate transitions in Africa.